Human Buildings for Human Beings: Inside the Movement to ‘Humanise’ Architecture:

Abigail Scott Paul in the UK explains why boring buildings are out and emotionally resonant, character-rich design is essential for public health and stronger communities.

Sander Schuur: Our project, the PGH Platform, focuses on how design can support human well-being and health. We think that design plays a key role in how people feel in a place, but generally we don't talk about this. For me as an architect, that's also the core of architecture – we are designing for people. When Thomas Heatherwick’s book Humanise came out in 2023 I said, my God, finally! I've been frustrated that for so long architects have been talking about everything except design.

I think that architecture in the last 20 years has been trying to find an identity where it does not exist. In that process we have tried to become specialists in everything, like now we're specialists in AI and all kind of digital tools. Nobody talks about design anymore.

And then suddenly there was a book - and a movement - talking about ‘boring architecture’ that causes people to feel less. So much to unpack here. To start our conversation, can you give an update about the Humanise campaign, why you and others at Heatherwick Studio started it, and what you have learned? Can you tell me more about where architects should be going as a design community to make a difference?

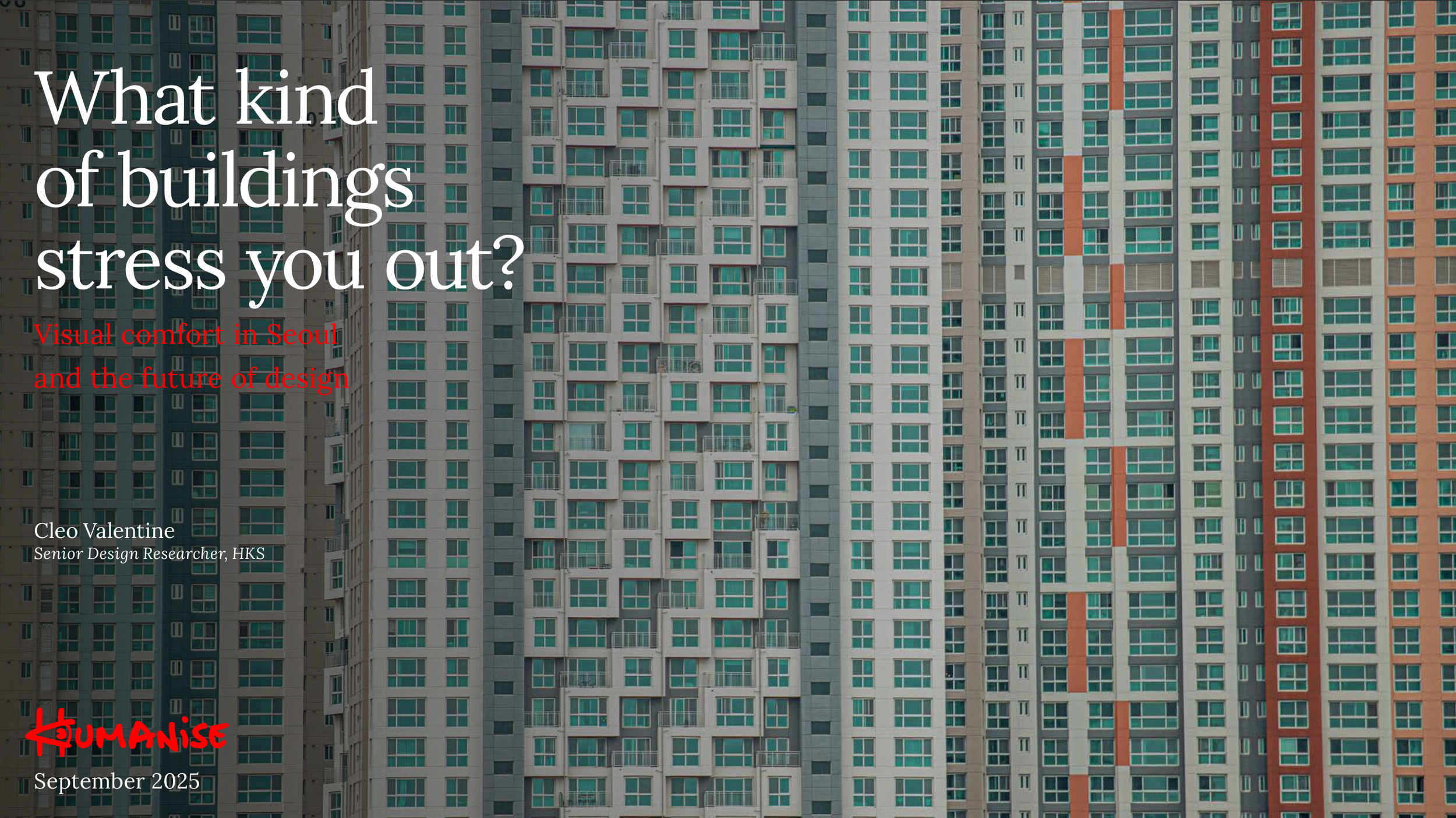

Abigail Scott Paul: There is a problem hiding in sight across the globe: monotonous, soulless and boring buildings are dominating our skylines and dragging us down. We know from research that dull development is bad for our brains and bad for society in general. The Humanise campaign is a 10-year global effort to draw attention to this problem and boost the public conversation about the need for more joyful, more human and more engaging buildings in our cities.

We're also trying to be a convener: to connect science with practice. Over the past two years, we’ve brought together neuroscientists, environmental psychologists and researchers with developers, architects, planners and shared insights from the science and explored together how we can design better buildings that can lift people up.

A building serves the users of that building, but also the public because structures are the backdrop of our lives. Thomas calls them the walls of public life.

“A building serves the users of that building, but also the public because structures are the backdrop of our lives. Thomas [Heatherwick] calls them the walls of public life.”

Schuur: Makes sense.

Scott Paul: We’ve done a lot of engagement with the design community and found significant agreement among architects that this is an issue and they want to do something about it.

We want to work collaboratively, so others can be strong advocates and messengers for change too. We look for architects who are doing something different, who are asking clients to add details and character to a project. By bringing people together, we are building a network and a movement.

It’s important to celebrate successes to show what is possible. We often hear: ‘it's all about cost, or the developers just wants us to do a redesign. We didn't design the whole scheme’. You have to counter that with how it can work, otherwise it feels like we can't change anything.

We're working with partners , like the health sector and the heritage sector in the UK. The latter is thinking about building the heritage of the future. It’s not all about going back to classical architecture forms or Georgian houses. We're asking, how can we build new buildings that have character, that tell stories about a place and its people?

I worked onLeeds’ Year of Culture, and know how culture and creativity in cities connects to so much of what we’re talking about: artistic expression, planning, health and well-being. A lot of city strategies are focused on that. We were invited to Oslo earlier this year as they are developing an architecture guide for the city and were interested in our Humanise Principles.

Schuur: Interesting.

Scott Paul: We are asking, how do we get the developers to shift their mindsets?? How do we get the city leaders or the councils to encourage and incentives more joyful and engaging buildings as part of their regeneration and redevelopment plans.?

Thomas was general director of the Seoul Architecture Biennale this year. The whole city dedicated itself to a public conversation around the design of buildings. There are mayors who are interested in this.

In the UK, our councils are so cash strapped. The whole country's been through a huge period of austerity since the financial crash in 2008 – which led to a lot of cutbacks at the local authority level. They don't have capacity for these conversations. We're hoping we can influence the new Mayors and the new government and their plans to build housing.

We interviewed over 1000 people living in England's new towns, for example, about how they think and feel about the buildings that line their streets. Only 4% of them described them as ‘nice’. We then visualized what a more joyful new town might look like, alongside creating an image of standard ‘boxy’ high street, and a more historic street. We asked the public, what do you think? Guess what? Nobody wanted the standard, boxy, soulless one.

“We visualized what a humanising new town might look like and asked the public, what do you think? We did a sort of boring version, a humanising version, a contemporary, and then an of old-fashioned one. And guess what? Nobody wanted the standard boxy, soulless one.”

There’s a lack of great social housing in the UK and there's been a real crisis recently about the standards of that housing. We also need to be talking about how to build more joyful housing – there should not be an absence of joy for the people and places who need it most. There's a real risk that we're going to build fast and build poor housing. It shouldn't look bad; it shouldn't look depressing; it shouldn't bring communities down. We know from discussions we've had that people can feel embarrassed bringing their friends and family to their houses because of how they look or how an estate feels. So why not try and do something different?

Schuur: You talked about guidelines. If an architect like me hears about neuroscience research and the effects of design on people – then I would like to translate those findings into design strategies or perhaps even principles or guidelines for me as an architect to be able to work with how the design will affect people. Do you address that in your guidelines?

Scott Paul: We developed five basic “Humanise Principles” that can be applied in different ways depending on the context. They were designed mostly for developers and city commissioners. One principle is ‘emotion as a function of design’.Design always produces an emotional response. Treating emotion as part of a building’s function helps to clarify intent and create places that feel welcoming, calming. What emotional response do you want people to have when people encounter a building?b By designing visual complexity into the façade through the use of materials, texture, details, you can help to generate a sense of meaning, belonging and welcome. You can focus visual complexity at three different scales: the city, like the silhouette; the street level; and at t door distance. If money is a problem, then we generally advocate for concentrating that visual complexity on the door and street level where most people experience a building.

We've worked with a planning consultancy to develop the principles to show where they're relevant in the UK planning system. We're hoping these might help kick-start other conversations.

Schuur: I have a question about complexity. Nature is obviously very complex - if you look at a tree and its leaves and branches, that is complex. We’re saying that being close to nature improves human well-being, like in a healthcare setting where it can help a patient heal faster after surgery. But as an architect designing for a healthcare environment, I would choose a more minimalistic approach.

So, I think it's interesting that you need a level of fascination. You need variation like in music.

Scott Paul: We’re not saying that every building needs to have all bells and whistles, or be iconic. We are saying the everyday buildings need to raise their game more and that context matters; where a building sits and what else is around it matters.

Schuur: I like that you are asking decision-makers to get into the conversation. How do you see the power of cities to ensure better quality design and how do you see the willingness of design developers to do the same thing?

Scott Paul: We're trying to work with the early adopters. Of course, we want everybody to take this on, but first we need to go with the flow where there are people that are expressing interest, like in Seoul. We know that there are mayors in the US who are interested in doing something different too.

We're finding it hard, however, to have the conversation with mayors in the UK because there's really no design conversation in the UK. It's strange because design is one of our greatest exports as a country and we've got great designers. I think there is still this attitude that design is ‘nice to have’ rather than delivering a basic need.

Working with like-minded partners helps get the word out in a variety of ways people can take in. For example, the heritage community, the sustainability community, the health community - if we work together to champion great design it can be heard in different ways.

It's also understanding the power of your message told by somebody else who is not perceived as having a vested interest. Having different messengers starts to build a narrative that becomes hard to drown out.

Catey Gans Kyrö: Do you think that this information can be too much to present to people? If you were to say, here's a map of how everything about the building and its users is connected, would that be overwhelming?

“We developed five basic “Humanise Principles. One is ‘emotion as a function of design’ - a building evokes emotion and you need to think about that when you design it. How? Adding visual complexity on the façade, and there are three scales: the city, like the silhouette; the street level; and the door distance.”

Scott Paul: Probably, so we have to tailor the conversation. With developers we have to prove social and health impacts, but also the commercial benefits. We need to demonstrate that designing for health and well-beingcan deliver economic benefits. That's why getting developers to talk about what they've done is important. If we can show real outcomes there will be more demand.

We need to get the economic analysis right – and that’s hard. Even with the benefits of the design, developers have to be able to deliver that building on time, on budget and generate a profit.

Schuur: Do you believe in convincing people to take this design approach, rather than forcing companies to develop a certain way as some cities have done?

Scott Paul: Yes, we're trying to not force or add more rules and regulations. We’re trying to shift a mindset, and to show there are alternative ways to build and design within existing guidelines.

Schuur: Some US cities have a point system. If you develop in a certain way, then you get points and with those points you can buy additional square footage or height. This allows the city to incentivize a desired outcome. Hamburg, Germany made a policy that you cannot build and then immediately sell. You must hold a building at least five years, making developers invest more in their building and the surrounding area. These approaches provide carrots for the developer. Can we trust that by raising awareness everybody will raise their standards?

Scott Paul: There likely must be a bit of carrot and a bit of stick. It requires somebody with a vision and desire to do something different, and then showing a vibrant, economically active place as a result, like the work we did in King’s Cross or Little Island in New York.

I think architects need to get better at telling these stories, showing what is possible, and shouting about it. I think it comes down to, can you sell a vision and persuade your client to do something that delivers a great place to live, work, play, and is also economically productive with social impact?

Through the Humanise campaign we want to see it become socially unacceptable in 10 years to build crap buildings that are unhealthy and unsustainable; that this sort of development is seen as an anachronism, and seen in the same way as fast fashion and fast food.

“We want to see it become socially unacceptable in 10 years to build crap buildings that are unhealthy and unsustainable.”

Kyrö: Are some of the best ways to share that message to connect with people in person, or through articles, media? What have you found to be the most influential so far?

Scott Paul: It's multi-channel, but being face-to-face is where I have gained the most confidence that we're on to something. I hear ordinary people talking about architecture. They can very eloquently articulate what matters to them and understand what we're talking about. We're trying to increase our digital media engagement and work with partners to share the story as well.

Kyrö: Where do you get the resources and time to do this? You’re only a team of three people and obviously this work takes a lot of time to research, create and analyze surveys, find partners, do all the media.

Scott Paul: We have a budget. The studio for now is the main funder, but we have had support from the Allen Institute in the US to help with research. And we're looking to identify more funding. But yes, it's a lot.

Kyrö: It is, and it’s also incredibly creative.

Scott Paul: It’s a very creative studio. We don't want our campaigning to be boring. We want it to be joyful and engaging.

Kyrö: And artistic.

Scott Paul: By sharing what we're doing on a beach in the north of England as well as Seoul, we show partners that we can apply this thinking to projects from a tiny English town to a major conurbation in East Asia.

That said, it is hard to cut through the information overload - the political instability in the US, geographic instability, geopolitical events, Ukraine, Russia, Gaza, Israel, the climate crisis. It's hard to make this issue seem as important. We have to sow the seeds, be patient, and build the movement so when the moment is right we can show up with something of value to say. For example, housing in the UK is an opportunity where we can have a conversation that is relevant and timely.

Schuur: Massively. I think you're talking about public outreach. If you read the language on your website and compare it with the language of neuroscience or architecture, I think it really speaks the words it needs to say.

Scott Paul: We've done a lot of work on our language because I'm a framing geek. In my past I've worked on how to ensure issues are heard in the way you want them to be heard. We're trying to make this very understandable for the general public. And you don't have to tell the whole story. Sometimes academics or professionals want to share absolutely every aspect, but actually no, you need to boil it down.

We're trying to have a public conversation and the public wants you to be really direct and articulate why this matters. The what and how is pretty easy to describe, but it’s the why that really matters to people.

“We're trying to have a public conversation and the public wants you to be really direct and articulate why this matters. The what and how is pretty easy to describe, but it’s the why that really matters to people.”

Kyrö: It is interesting that in this geopolitical climate, there is a lack of self-efficacy. It's as if people need to know that they can make a change or a difference. So ‘why does this matter’ is that first step, and then we have to provide solutions as to how.

Scott Paul: We know our proposition: we're saying human beings need human buildings. It's a need - not a want, not a deserve. We need it for our health, for the environment. I think as the campaign grows we'll develop tools for individuals. If a building is proposed for your community, here are some of the things that you can do to self-advocate. We'll get to that stage, but we haven't done that yet.

First, we need to understand what individuals can do on their own. For the next three years we're focusing the public at a macro level and the profession. Then in years 5 to 10 we’ll get into the community - how people can self-advocate, what tools they need, and the interest groups that can help be a bridge.

Schuur: The Pittsburgh Platform is an umbrella organization, attracting different viewpoints and sharing information to foster these dialogues. Given you’ve been doing your campaign longer than us, is there anything specific you think we should do or not do?

Scott Paul: First, I think the more the merrier. Sharing one another's work would be good. We can share relevant information in our newsletter and social media, for example.

Second, you can't expect people to come to your platform. You have to seed your campaign on other people's platforms. That is how you get reach. So look at who else could be your messengers. You've also got to tell your own story very well and do it regularly. You can't just rely on others.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.